Interview with James Curry on his biography of Ernest Kavagh

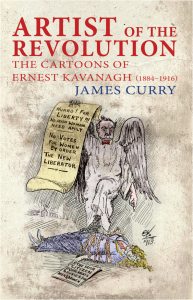

- Front cover of James Curry’s book Mercier Books Price €11.69

Who was Ernest Kavanagh and why was he significant in the era of the Lockout?

Ernest Kavanagh was an insurance clerk who worked for the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) in the four years or so prior to his fatal shooting on the front steps of Liberty Hall during the Easter Rising. He was a civilian casualty rather than a combatant, and his significance lies in the fact that he also happened to be an important cartoonist. Most of Kavanagh’s illustrations appeared in the ITGWU’s weekly paper, The Irish Worker, which was edited by James Larkin, apparently a good friend of his. Yet Kavanagh also contributed cartoons to other nationalist and suffrage papers from the period such as Fianna, Irish Freedom and The Irish Citizen. James Connolly, Seán O’Casey and Countess Markievicz were among those who admired his work.

What do you say to critics who claim that Kavanagh was a poor draughtsman with his work having little artistic merit?

That they’re being a bit unfair on Kavanagh and, at any rate, missing the point. That’s something I discuss in Artist of the Revolution. I understand why some people would look down on his cartoons, which were usually rather sharply drawn and hard-hitting in nature, but they were very unique and usually perfectly suited to his target audience. For example, Kavanagh contributed over thirty cartoons to The Irish Worker, which was a paper known for its fiery defiance and transparency of expression. Nobody who ever read James Larkin’s editorials was left in any doubt as to where he stood on an issue, and the same could be said for most of The Irish Worker’s contributors. Kavanagh’s cartoons, most of which appeared on the front page of the paper, were visual representations of this writing style and that’s why he was Larkin’s perfect cartoonist in my opinion.

Maeve Cavanagh, who spelt her surname slightly differently to her brother, was a fairly prominent nationalist and labour poet during the same period. How important do you think she was in Ernest’s political and artistic development?

Well in terms of artistic development, she appears to have acted as something of an unofficial agent for Ernest at the beginning of the century as we know that she wrote to Arthur Griffith at one point asking him to take a look at some of her brother’s cartoons. Then later on, following the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, she and Ernest worked very closely together to produce a series of anti-recruitment cartoons and accompanying poems in The Irish Worker. Politically they were very similar in that they were fierce nationalists, both working as anti-recruitment propagandists during the War and both supporting Connolly’s decision to launch a rising in 1916. This isn’t surprising when you consider that their father had been a Fenian organiser and they grew up in a household where Wolfe Tone was idolised. But there were also differences between them. For example, Maeve had no interest in the suffragist movement whereas Ernest contributed a number of cartoons to The Irish Citizen which attacked the injustice of Irish women not being allowed to vote. Also, Ernest was primarily associated with Larkin and known as a labour cartoonist – mainly due to his notorious depictions of William Martin Murphy and the Dublin police in The Irish Worker during the Dublin Lockout – whereas Maeve was primarily known as a patriotic poetess who was championed by Connolly in The Workers’ Republic. The closeness of their relationship is obvious when one reads Maeve’s poems about Ernest written in the years after his death, several of which I’ve included in my book.

How important was The Irish Worker and other publications such as The Irish Citizen, that he worked for?

Very important. For historians interested in the Irish labour and suffrage movements a century or so ago they are absolutely crucial newspapers. Yet they should not just be seen as important sources. In my opinion both papers you mention played a key role in organising their respective movements and were very influential publications. Certainly, we know that The Irish Worker was monitored very closely by the Dublin Metropolitan Police and Dublin Castle who were constantly worried about its potential to incite violence.

Finally, how would you assess the impact that Kavanagh’s cartoons had on Irish public opinion?

Well it’s important to note that his cartoons were mostly at odds with mainstream Irish opinion at the time that they were first published. It was only a few years after Kavanagh died in the Easter Rising that Ireland really began to turn on William Martin Murphy and John Redmond, who were the two figures he most persistently attacked in his cartoons. By and large I think it’s more appropriate to say that Kavanagh reflected certain opinions rather than necessarily influenced them. But there’s no doubt that his cartoons were a potent weapon and his most powerful depictions of Murphy, Redmond and the Dublin police created images that stuck in many people’s minds for years afterwards. I think it’s telling that, when Murphy’s lawyer was complaining about the public persecution his client had to face from Larkin during the Askwith inquiry set up to try and bring an end to the Dublin Lockout, he held up to the courtroom The Irish Worker issue from September 1913 that featured a large front page Kavanagh cartoon of Murphy depicted as a murderous vulture as proof.