Sleeping on Dynamite: Casimir and Constance in 1913

This extract from Pat Quigley’s new book ‘The Polish Irishman: The Life and Times of Count Casimir Makievizc (Liffey Press) gives a flavour of this beatifully written and unusual take on Bohemian Dublin in the years leading up to the Easter Rising. Colourful characters, arcane organisations and the dog taken prisoner of war in 1916 are just some of the gems, not to mention new pictures of Constance, Casimir and their coterie.

Beginning

Dublin 1913 conjures up images of policemen rioting in O’Connell Street, strikers attacking trams, hungry people on the quays and tenements falling into the streets, but for the couple who lived in 49B Leinster Road, aka Surrey House, that January started much the same as any other.

Thoms Directory listed the head of the household as Casimir Markievicz. While his neighbours had solid occupations like solicitor and merchant he was described as “Count and United Arts Club.” He was on the committee of the Arts Club, but it’s hard to imagine how being a count could be an occupation. Maybe he wanted to have a little joke and simplify things for the Thoms researcher. A list of his occupations up to that time would include: artist, racing cyclist, playwright, theatre director, stage manager, fencing instructor, journalist and author.

His wife, Constance, could claim a similar list of activities: artist and art teacher, actress, philanthropist, feminist, labour activist and, in the eyes of Dublin Castle, an encourager of general mayhem. She did not use the title Countess, but preferred, like her associate Maud Gonne, the neutral term, “Madame.” She spent much more time in the house than her husband; for the past ten years he left Ireland for a few months each year to visit his family in The Ukraine. The Markieviczs were an unconventional couple, known to their friends as Con and Casi.

Neither could guess that the year 1913 which began so quietly would end with Irish society shaken to the core. They would make decisions and choices that would determine the paths they would follow for the rest of their lives.

Surrey House presented a tranquil redbrick face to the world, but the neighbours were used to eccentric behaviour. Casi once bought a supply of theatre wigs: he cleaned them and left them to dry on the windowsill. Sometime later Con became aware of people standing on the road talking loudly about human scalps scattered over the flowers and the lawn. They left a window unlocked at night so that any wandering friend in need could climb inside. The house was like an art gallery with many of their paintings on the walls. There was the Ukrainian picture, Bread, Con’s favourite among Casi’s paintings. It hung beside scenes the couple painted in Zywotowka where Casi built a studio in the park. Among them was Con’s painting, The Conscript, inspired by real-life events and Casi’s portrait of the artist’s wife which now hangs in the National Gallery of Ireland.

While Casi was on his travels Con turned Surrey House into a centre of political agitation. She rolled up the carpets and made it an open house to republicans, socialists, suffragettes and the occasional poet. Her only child, Maeve, was in the care of her grandmother in Co Sligo. Her stepson, Stasko, had finished secondary education and was staying with her sister Mabel in Kent. The G men, the Dublin political police kept watch from a discreet distance. (Rathmines was still respectable in those days.)

Con started the year 1913 with a controversy in the correspondence columns of the Irish Times. The debate wasn’t on any of the pressing issues of the day – tensions over Home Rule and the threat of civil war in Ulster, the violent suffragette campaign demanding votes for women or the intermittent war between workers and employers. The newspaper of 1 January featured her letter supporting Lennox Robinson, Manager of the Abbey Theatre, against the critic Ernest Boyd. Boyd had criticized the national theatre for failing to carry the banner of cultural nationalism and accused it of relying on farce and melodrama to attract audiences. It was the old debate of popularity versus quality.

Con adopted the tone of a schoolmistress to a difficult, but not quite hopeless, pupil: ‘The balance sheet should prove that Lady Gregory and Mr Yeats have not made fortunes out of the enterprise, but have generously given their time and talent to the work of building up Irish dramatic art…Their work is to create an Irish theatre. They began with nothing, no plays, no actors – nothing but their own brave hearts.’

The letter has all the marks of a determined attempt to mend relations with the Abbey. After they settled in Dublin in 1903 Con and Casi supported the setting up of the national theatre. Con later fell out with Willie and Lady Gregory, who accused her of meddling in the Abbey. Con joined the breakaway Theatre of Ireland and acted in their plays. Casi added to the offence when he defended Con after Willie accused the new company of making off with £50 that belonged to himself and Lady Gregory.

By 1913 there was a thaw that enabled Con to end her letter on an upbeat note:

‘They gave us what they can; we must help them to give us more. All honour to Mr Yeats and Lady Gregory and their little band of pioneer authors and actors, and all success to them in their uphill task.’

I’m not sure if Lady Gregory found the term “little band of pioneer authors and actors” condescending; she had a stern nature and a long memory.

‘If you intend to dine with the Markievicz pair,’ she warned Willie, ‘be sure to bring a long spoon.’

On Friday, 3 January, Casi attended a meeting of the Mansion House Committee in support of a Gallery of Municipal Art. The committee had been set up the previous November to support a Dublin gallery for the collection of paintings donated by Lady Gregory’s nephew, Sir Hugh Lane, on condition that Dublin Corporation would provide a suitable building. The committee included a number of other prominent citizens – the artist Sarah Purser, surgeon and wit Oliver St John Gogarty and Lady Fingall.

Lane said he became an Irish nationalist when he discovered the windows of the Vice-regal Lodge couldn’t be cleaned without an order from London. The problem was his insistence that the citizens of Dublin provide a suitable gallery for the pictures. The existing building, Clonmell House, in Harcourt Street was in poor condition. Lane had his heart set on a gallery across the Liffey to a plan designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens.

Casi and Con knew Lane well and had campaigned on his behalf for the last ten years. In 1904 Casi opened a public meeting in support of Lane with a speech in French, followed by Willie Yeats and George Moore. Casi painted his sensitive portrait of George Russell/AE for the Lane Collection. Other pictures in the collection include a portrait of the first president of UCD, George Coffey, a landscape study and a distinctive painting of a Ukrainian village in the Crawford Gallery in Cork.

The Mansion House Committee was not perturbed by agitation against the gallery by a group of Dublin ratepayers. Their spokesman was a sixty-seven year-old businessman, supporter of Home Rule, President of the Rathgar and Rathmines Musical Society as well as a keen golfer and yachtsman. He controlled the Dublin Tramway Company, the Irish Independent group of newspapers and some hotels and would become the most notorious Irish businessman of the Twentieth Century, William Martin Murphy.

Murphy’s opposition can be seen either as philistinism or as an assertion of the catholic middle-class against the influence of the Protestant ascendency. The undercurrent of Catholic versus Protestant intensified when Yeats entered the fray with a poem in the Irish Times:

“You gave, but will not give again

Until enough of Paudeen’s pence

By Biddy’s half-pence have lain.”

Murphy was not intimidated by Willie’s high tone and took up the cudgels on behalf of Paudeen and Biddy. He criticized a handful of dilettantes for promoting a gallery for which, he claimed, “there is no popular demand and one which will never be of the smallest use to the common people of this city.”

He attacked Lane for trying to offload pictures he couldn’t sell and of seeking a monument to himself. He opposed the Liffey proposal on every possible ground – the architect was English; the foul and damp air from the river would spoil the canvasses; it would block the view of the sunset from O’Connell Bridge.

‘I would rather see in the city of Dublin one block of sanitary houses at low rents replacing a reeking slum than all the pictures Corot and Degas ever painted,’ he declared.

Despite Murphy’s opposition Dublin Corporation met in January and passed a motion to levy a rate of one farthing in the pound to erect a Municipal Art Gallery “for the purpose of housing the magnificent collection of pictures kindly given upon certain conditions by Sir Hugh Lane and others.”

Casi was deeply embedded in the artistic and cultural life of Dublin. In the ten years since he came to live in the city he had founded theatre companies, written popular plays at the Abbey and the Gaiety. He brought plays by Shaw and Galsworthy to Dublin and helped to stage many others. He and his wife were at the centre of a group of actors and writers. He founded the Irish Fencing Society, painted numerous landscapes and portraits, and collaborated with other artists including AE, William Leech and Francis Baker in annual exhibitions. Along with Con he helped to found the United Arts Club in 1907.

In early 1913 he was busy with plans for a new theatrical venture, the Dublin Repertory Theatre, an amalgamation of three dramatic groups. He was co-director with the actor, Evelyn Ashley, who was related to Con. He had his office in Davy Byrne’s where, in the company of the Gaiety carpenter, Martin Murphy, he would rewrite plays to make them more presentable. When he was in a good mood, which was often, he would refer to the new company as The Dublin Reformatory.

Con was involved with nationalist, suffrage and labour causes since 1908. Casi wrote his most successful play, The Memory of the Dead, in 1910, which allowed her to act her dream of working to free Ireland. Her growing identification with militant groups had a negative effect on Casi’s career as a portrait painter. Despite the growing notoriety of the Markievicz name he maintained contacts on all sides.

When he came to Dublin with Con they attended parties at the Vice-regal Lodge in the Phoenix Park. He sang Polish songs as she accompanied him on the piano in the town houses of the aristocracy around Stephen’s Green. By 1913 the parties were usually in the smoky surroundings of The Bailey, Davy Byrne’s or Neary’s. He was always welcome in the United Arts Club building at 44 St Stephen’s Green and often used it as an address. He often stayed here with his friends, Ellie and James Duncan, and regularly dined with Gogarty at his home in Ely Place.

The early 1900s was a golden age for the culture of the public house. Drink was cheap and private houses had no central heating. The pub offered the attraction of genial company with aspiring artists and writers. Everyone seemed to have a classical education and could quote Homer in the original. It is a vanished Dublin, celebrated more in the novels and memoirs of Gogarty, than the much darker work by Joyce, which has eclipsed him. Drink was part of the fun, but there was much versifying, storytelling and discussion of art, life and literature.

Casi was a large man and his social world was shrinking by 1913, but he didn’t complain; ‘it will do well enough’ was a favourite phrase.

Spring

One of the diversions of Dublin was the Reality League. It appears to have been a riposte to the many organizations with more serious intent that flourished at the time. The name is intriguing; it implies an aspiration to go beyond the struggles of nationalist and unionist; worker and capitalist. As a man from the Borderland Casi knew of the artificial nature of identity and the Reality League implies a purity of heart and a sceptical way of looking at the world. The title is almost a synonym for Sanity League, a civilized grouping in a world lurching towards chaos and war. Little remains of the League – two invitation cards and a brochure of poems. It is like one of those magical islands in folklore that appear in the sea at sunset. You can see features and people moving about and then it disappears for a hundred years.

In early January the League sent out an invitation card designed by Casi to celebrate the arrival of spring with a fancy dress ball. The elaborate card reads like a manifesto: “We only believe in the god who knows how to dance” is broadcast across the top like an election slogan.

“Do you want to bury your sorrows or reputation? If so, come to the Fancy Spiritual Meeting of the Reality League to be held on Saturday, 1st February, at 8.30pm in the Antiquarians Hall, 6 St Stephen’s Green.”

It was to be a fancy dress party – “mufti (civilian dress) not accepted.” Turkey Trot and soicalled dancing were allowed, but “antics and classical dancing preferred.”

The League had their own lexicon: “Slopping and mauling” were strictly prohibited in the dancing room. It begs the question as to what exactly was involved and if such behaviour was tolerated in other rooms. He requested “inveterate sitters-out … to provide your own furniture” and added: “A Mortuary for intaxicated (sic) brethren will be provided, Charge 3d per Hour.”

The slightly-mocking tone gives an idea why Lennox Robinson and Lady Gregory sniffed at the bohemian behaviour which they saw as rowdyism for its own sake.

Michael Gorman was a young student who appears in a rare Reality League photograph in Georgian costume along with what appears to be Con disguised as Maid Marion. The members of the Reality League were a roll-call of Casi’s Irish friends – Gogarty the poet, classicist and legendary Dublin wit; Seumas O’Sullivan – pharmacist, poet and bibliophile, author of a short poem linking Casi with a Dublin legend:

“Beyond the mud and purple of our town

You saw the hills eternal smile and frown,

And with your mighty spirit lighted then

The flame that beckoned back to earth again

The souls of Whalley and all his gentlemen.”

Another stalwart was James Montgomery, father of the poet, Niall Montgomery. He wrote a poem about one of the League who was leaving for London celebrating their favourite public houses:

“No more at eve in the ‘House of Laurels,’ no more at noon by the Scottish Weir,

Will Red Branch Knights emulate his morals, while quaffing goblets of ginger beer.

Now London Johnnies will ape his costumes, his hippy coats and creased pants;

They’ll grow moustaches like hairy walnuts, and swap their canes for his neat ash plants.”

“Hippy coats” in 1913? Jimmy was a prophet as well as a poet.

There was surely an overlap with membership of the United Arts Club. I suspect another member was Tommy Furlong, a solicitor who lived next door on Leinster Road. Where did the elephants come from? A letter to Gogarty in New York places them on a building at the corner of Dawson St and Nassau St. This appears to have been Morrison’s Hotel which was demolished and replaced with modern shop and office units.

The slogan at the end summed up Casi’s philosophy: Long Live Life.

The activist and friend, Helena Molony, gives a picture of the relationship between Con and Casi at this time:

‘Whenever he was back in Ireland he came to her house, “Surrey House.” She was always delighted to see him coming. I should say that their love affair had gone off the boil; but she was really rather proud of him…She would be delighted when he would be coming home and would say: “I’ll be having him on my hands,” but she would really be rather pleased.

He would spend about half the year here in Ireland. He was a very colourful character. He would paint the town red. He would have…his ‘flying column’ about him, young men about town writing plays and painting pictures.’

Their friends noted the cracks in the marriage and speculated whether one day he would go off and not come back. Molony’s comment about the marriage having “gone off the boil” was a polite way of saying they didn’t have sex anymore. Rumour had it that sexual relations had ended after Con nearly died when giving birth to Maeve in 1901. She later told a friend that she didn’t have sexual relations with Casi from that time. We have no way of knowing the truth of the rumour, but Casi returned to Ireland each year with renewed enthusiasm. There’s a lot we don’t know about them. Private life in those days meant just that, but it appears that the sexual passion of the Paris years had mutated into a deep bond that held them together.

Friends remembered that Con used to repeat a phrase: “I don’t know why Casi married me.” She said it so often nobody paid any attention until one day Casi lost patience and snapped: “he didn’t.” She never used the phrase again. Later he explained that she had pursued him in Paris in 1899 and pushed for marriage. It annoyed him that she was suggesting it was the other way about.

He might spend too much time in the pubs and be a midnight wanderer, but he was still her Borderland prince, her soul mate from the exotic East. She was becoming increasingly absorbed in politics, but missed him when they were apart and wrote often about him in her letters.

Casi was a fellow who brought joy wherever he went. When asked if he was tempted to stay in Poland he replied that Dublin was his home; there was no city quite like it with the tidal waters flowing through the centre and beautiful blue mountains beckoning from the end of every street. His other home was far away in the centre of The Ukraine – Zywotowka, which he called “the place of life.” He would travel between the “the place of life” to the city of Anna Livia, the river of life, where he could consume vast amounts of uisce beatha, the water of life.

Long Live Life!

He was full of ideas for the Dublin Repertory Theatre which would put on the best modern theatre. He saw the theatre coming under threat from the new medium of film. The big cinema attraction in 1913 was the first blockbuster Quo Vadis? It was a full two hours long and based on the book by his countryman, Sienkiewicz. He decided to meet the challenge from the cinema by putting on lavish productions with elaborate sets, exotic locations and large casts.

Con announced the new company in a letter to the Freeman’s Journal in April:

“The new Repertory company … does not deign to go into competition with our other repertory theatre, the Abbey, but seeks to be … its complement. It proposes to put on plays of the modern European and English stage which one ordinarily does not see produced by the commercial theatre in Ireland.”

Casi threw himself into planning a busy schedule of plays in the Gaiety Theatre. He particularly liked works by Shaw which dramatised ideas and he derided superficial critics for calling them “talky talky” plays. Shaw was a controversial, even subversive figure, in 1913. He provoked people to think and his plays were often banned and censored. He hit the mark in relation to Ireland when he wrote in John Bull’s Other Island:

“A healthy nation is as unconscious of its nationality as a man of his bones. But if you break a nation’s nationality it will think of nothing but getting it set again.”

Casi also planned to produce plays by John Galsworthy, then known primarily as a writer of social dramas such as Strife and The Silver Box.

Con was taking smaller roles in his productions; she was deeply involved with Na Fianna scouts and, when weather permitted, took them on manoeuvres in the Dublin Mountains. She was also a member of Sinn Fein, the Gaelic League and the Women’s Franchise League.

Another project involved the provision of school meals for hungry children. Maud Gonne wrote to the Irish Times in January that hundreds of children died of starvation in Dublin each year. Con helped her to set up a scheme for free school meals in St Audoen’s and John’s Lane schools.

She also helped her friends who were organizing the unskilled Dublin workers – Jim Larkin and James Connolly. Con had been a follower of Larkin’s since she heard his passionate oratory and described him as “a Titan who might have been moulded by Michelangelo.”

She was involved in so many activities that people nicknamed Surrey House as Scurry House. Lennox Robinson caricatured her as Isabel Moore in his novel: A Young Man from the South:

“She was secretary or president of innumerable clubs in Dublin – clubs for working girls, women’s suffrage, feeding school children and I don’t know what others…They often passed me on bicycles in the evening going from one meeting to another, Isabel on a very muddy old bicycle with a torn tweed skirt which her furious pedalling worked up to her knees showing her beautifully shaped leg and ankle.”

Casi introduced a lecture by Yeats to the United Arts Club in March 1913 on The Theatre and Beauty. He was also involved with Gogarty in putting on an exhibition of the work of the Fauve artist, Harry Phelan Gibb. Gibb lived in Paris where he was a close friend of Gertrude Stein and Matisse. His Irish mother made him the only Fauve artist of Irish extraction.

An exhibition of Gibb’s work in Paris had been successful and the organizers hoped to replicate it in Dublin, the new art capital of the west. They didn’t reckon on clerical opposition to the nudes in the collection. The Dublin police closed the exhibition before the opening and confiscated the nudes which were only returned to Gibb in the 1930s. The episode shows that Casi was still involved in the art world and was interested in modern painting.

In April the Dublin Repertory Theatre put on Francis Coppee’s For the Crown, a melodrama set in the Balkans during the Middle Ages. The play involved a large cast in exotic costumes, battles between Christians and Turks and an elaborate set which included a huge statue of a horse. It was a great success.

Summer

He followed it in May with Shaw’s The Devil’s Disciple. This was set in America at the time of the Revolution and involved a plot of mistaken identities. The play called for a cast of 50 which included British soldiers and American rebels. Casi added to the realism of the play when he recruited Unionist students from Trinity College to play the Redcoats and from Constance’s Fianna to be the rebels. One critic said that the fight scenes were the most realistic he ever saw on stage.

The play could be performed as melodrama or comedy and the director went for the latter. It was well-reviewed, especially the performance of Breffni O’Rorke, who would become a successful film actor and step-father of Cyril Cusack. Con was busier than in the past, but played a small part. She appears in wig and bonnet beside Casi in photographs of the cast. He is the only one not in costume, a cocker spaniel in his lap. It is the last photograph we have of them together.

There has always been speculation about Con’s lovers after Casi. The names tumble out – Connolly, Larkin, Eamon DeValera. In fact the photograph says it all. The Markieviczes loved dogs and this particular cocker spaniel, Poppet, became the main object of her affections. He went almost everywhere with her, sometimes to the annoyance of Na Fianna, one of whom ungallantly described him as “an oul dog you’d love to root.”

I don’t think Poppet was on duty in St Stephen’s Green, but he was present at many crucial events. He was with Con when she was arrested by British soldiers who brought them to the barracks. A problem soon became apparent. There was no law whereby a dog could be charged with treason. Not only was Poppet’s detention illegal, but could make the authorities look foolish. So Poppet was delivered to Con’s sister, Eva, under armed escort. His part in her life is commemorated in the fine statue on Townsend Street. If only dogs could talk, what a story Poppet could tell.

When the run ended the cast celebrated with a birthday party for O’Rorke in Surrey House. O’Rorke supplied the whiskey, Casi the champagne and Con the beer and food. She baked a huge tier cake with the inscription: Long Live the Devil. The party went on until the early morning. At a late stage Tommy Furlong announced he was going to sing: God Save the King. When Con threatened to empty the tea-urn over him he went next door and changed into a bathing suit. He came back and sang the anthem as she poured lukewarm tea over his head. O’Rorke took Furlong outside and set him down gently to sleep in the garden.

Dublin was simmering beneath the surface. The poverty was among the worst in the world and the slums were compared to Calcutta. Infant mortality was the highest in the United Kingdom; thousands of families lived in single rooms. Wages were low and prostitution was encouraged because of the huge British Army presence. Corruption was rife – the vote was limited and many city councillors and officials were slum landlords. On summer evenings the poor would emerge from the side-streets to fashionable squares and watch the “quality” driving past. Side by side with gruelling poverty was a world of town houses and servants, afternoon tea in the Shelbourne and the style at the Horse Show. The middle classes mostly lived in the growing suburbs of Glasnevin, Clontarf, Rathmines and Rathgar.

A series of strikes led to an increase in the members of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union. James Larkin was the General Secretary, a Syndicalist, who believed that the creation of one organization for all workers would lead to the overthrow of capitalism. He struck terror into businessmen, nationalists, churchmen of all denominations and trade union leaders, all of whom would become redundant in the new dispensation. The employers were alarmed at the use of the sympathetic strike weapon.

Dublin employers were vacillating, but their leader, William Martin Murphy, used the same determination he brought against Lane to crush Larkin. He used his power as President of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce and leader of the Dublin Employers Federation to plan for the elimination of the ITGWU from the workplace. The battle would become one of ideas – whether capital or labour would dominate Dublin and thereafter the Home Rule parliament everyone expected. It was one of the few times in the history of the city when competing ideologies would be personified in two dominant individuals.

“The sole issue is whether Mister Larkin is going to rule the trade of Dublin, and whether people could carry on their business, or call their souls their own, without consulting Mr. Larkin,” he wrote.

The discipline Murphy imposed on his operations would have been severe even by mediaeval standards. The pay for tram-workers was above the general low level, but men could be sacked or suspended for a wide range of trivial offences. The company skimped on repairs to trams and men had to drive at dangerous speeds and take risks for which they could be sacked. The regulations were numerous and often unworkable, imposed by a small army of inspectors. There was always a huge pool of unemployed to take the place of discontented workers. Murphy controlled his workforce by dismissing employees for slight infringements.

The early months of 1913 had seen increasing confidence by unskilled workers as those who joined the ITGWU saw their wages increase by 20-25%, which restored their purchasing power of 1900. The employers’ method of keeping wages low was the pool of unemployed who were desperate enough to work under almost any conditions. Larkin counteracted this advantage with the sympathetic strike whereby an employer could find himself and his goods blacked by workers across the city. Larkin saw the sympathetic strike as a stage to a syndicalist society.

Larkin kept up a personalized campaign against his opponent and used the columns of the Irish Worker to refer to Murphy as: “… the most foul and vicious blackguard that ever polluted any country” and “a creature who is living on the sweated victims who are compeIled to slave for this modern capitalistic vampire.” He went on: “I prefer to go to the Seventh Pit of Dante than go to Heaven with William Martin Murphy.”

Murphy’s responses were usually weaker; he referred to Larkin as “the labour dictator of Dublin,’’ but he had the greater power.

Soon after the party for O’Rorke, Casi left Dublin for the summer. His friends held a party in his honour in the Dolphin Hotel in May. They presented him with an engraved gold watch to show their appreciation of his work in the Irish theatre and ‘of his genial and vigorous personality.’

Casi had become a journalist in order to make ends meet. Europe was drifting towards war and conflict in the Balkans could set off a conflagration, but first he had to go to the Place of Life. He said he could earn enough in Kiev to keep him going for the rest of the year. He may have been homesick for a land that is breathtakingly beautiful and the people open and welcoming. Maybe he needed The Ukraine to renew him. Around this time the gossip begins that he was a secret agent. He had the knack of gaining access to people at the top. Was he working for the Russians, the British or the Americans? We’ll never know for sure, but I doubt it.

When he went to Ukraine in 1913 he found a Polish revival taking place in the Russian Empire. After years of repression the Tsarist authorities sought to appease the Poles. The next war would be fought on Polish territory and it was vital to have popular support. Poles dreamed of an autonomous Poland within the Empire, the Kingdom on the Vistula.

Casi was beginning to feel a renewed patriotism that would lead to him joining the Russian Army on the outbreak of World War One. His literary energies revived and he began writing a play in Polish for the first time. The Wild Field was a satire on Polish landowners in The Ukraine and caused a scandal when performed. He made contacts in Warsaw and arranged to have the play put on the following year.

Meanwhile Irish nationalism continued its gradual organizational revival. Con found a loyal organizer in the young Liam Mellowes. The intense young patriot travelled the length and breadth of Ireland on his bicycle to set up branches of Na Fianna. His diary for May 1913 is typical:

“May 9: rode out to Castlecomer (10 miles). Roads knee deep in mud. Met several local Gaelic Leaguers but could get none of them interested in Fianna. Returned to Kilkenny.

May 17 saw him in Gowran (Kilkenny), Dungarvan (Waterford) and Borris (Carlow): Left Borris 8.30 to ride back to Wexford (38 miles) across Blackstairs mountains. It was black and no mistake. Rode through the night. Arrived Wexford 12.30. Total of miles for day, 62.”

The summer of 1913 began with a wet May – rain every day for a week Mellowes reported, but July and August were long and hot – it was the last golden summer of the old European civilization before the Great War changed everything. Con took advantage of the good weather to bring her scouts on manoeuvres in the Dublin Mountains. The scouts enjoyed the camaraderie of living in tents while Madame organized lessons in scouting, orienteering and first aid; the older boys could look forward to shooting and bayonet practise.

They were back in the city for the Ard-Fheis in the Mansion House where a group photograph was taken on 13 July. Con is the only woman in the centre of rows of boys and young men, flanked by Liam Mellows and Con Colbert. Sprinkled among the ranks are five young women in uniform. Despite the high ideals there was a lot of opposition within the organization to female scouts. Con fought for equality, but was over-ruled. The young women in the photograph are from the Belfast branches who were allowed to remain.

Many Irish people looked forward to the arrival of the Home Rule parliament. The Unionist revolt in Ulster was a worry, especially to Southern Unionists who feared becoming a minority in a Catholic state. Some Dublin Orangemen prepared for the worst and one group acquired a hundred rifles which they stored in behind Orange Order Headquarters on Parnell Square.

The controversy over the gallery kept smouldering over the summer. Lane gave a newspaper interview where he compared his opponents to “Goths and Vandals, Huns and Visigoths, who don’t know what is ugly or nice.” Yeats spoke at an Abbey Theatre benefit in July: “If Hugh Lane is defeated, hundreds of young men and women all over the country will be discouraged…Ireland will for many years become a little huckstering nation, groping for halfpence in a greasy till.” The dispute over the Dublin gallery had become a battle for the soul of Ireland. Larkin proposed a motion at the Dublin Trades Council in support of the gallery.

“Martin Murphy,” he said, “should be condemned to keep an art gallery in hell.”

Even the United Arts Club got involved with a special revue:

“On the banks of the Liffey water,

Where the main drain meets the sea:

That’s the very place we oughter

Build our gallery.”

Lady Gregory returned from America with a bag of money for Hugh’s gallery to discover everything up in the air.

‘Ah Hugh,’ says she, why don’t you let it go and put them in the Mansion House.’

Lane got in a huff and accused her of a lack of aesthetic taste. It was the Liffey or nothing. She was so fed up with the whole business that she urged him to pack up the lot and sell them at Christies.

‘That will show them,’ says she.

Autumn

The Dublin Lockout began on 15 August when Murphy entered the dispatch office of the Irish Independent and sacked 40 men and twenty boys for belonging to the union. Larkin responded by calling tramway workers out on strike on Tuesday, 26 August, in the middle of Horse Show Week. Workers walked off trams and left them blocking busy junctions. Murphy had relief crews out to take the place of the union men. The strikers and their supporters began to picket and obstruct trams. The Dublin Metropolitan Police were deployed to protect the trams and the workers who stayed on duty. The situation became more tense and then violent as slum dwellers became embroiled in violence with the police.

Casi arrived in the tense city on Saturday, 30 August. In his absence the Dublin Repertory Theatre put on Strife by John Galsworthy in the Gaiety Theatre. Casi was credited with recruiting dockers to perform on stage, but it is doubtful if he could have managed this from abroad and the story is probably based on gossip about The Devil’s Disciple. He arrived at Kingstown and was met at Westland Row railway station by a deputation from the Reality League. The party hustled Casi to Duke Street and brought him up to date. The constabulary and the citizenry belted each other in nearby Townsend Street as his friends told of the latest objections to Lane’s Gallery on the Liffey. It would block the Liffey sunset which God Almighty had painted and no artist could match. The Gallery would disturb the motion of the sea-breeze which was the only means of preventing an outbreak of disease in the filthy alleys. Casi must have wondered if it was the effect of the unusually hot weather or if his adopted country was going slightly off the rails.

After some refreshments the party made their way to Surrey House. He found his wife and a number of trade union leaders. The police were preparing to raid to arrest Larkin for defying the banned meeting. Casi and his party filled the house and defused any chance of a successful raid.

The main topic over breakfast was how to get Larkin into the city centre, which was swarming with police. He wanted to be conveyed in a hearse and to leap from a coffin like Lazarus from the dead. No undertaker could be found to supply a hearse. Con persuaded Casi to use his make-up skills to disguise Larkin as an elderly gentleman with a false beard and powdered hair. As they were of similar size Casi reluctantly loaned his morning coat and top hat along with his briefcase and trunk, both marked with a huge letter M.

Sean O’Casey was among the crowd in Sackville Street with a bandage in his pocket. He knew the police were supposed to hit with their batons on the shoulder, but usually went for the head. There was a roar as Larkin appeared at a window of the Imperial Hotel, dressed in what he thought was clerical garb, pulling out his beard and shouting that he had kept his word. Larkin disappeared into the hotel as police rushed inside to arrest him.

A crowd of on-lookers gathered outside the hotel entrance. There was some delay as Larkin realized he had lost Casi’s silk hat and the police helped him to look for it. Casi and Con were across the street in an open carriage with Helena Molony and Sydney Gifford. They went towards the hotel entrance as two policemen led Larkin through the door. Accounts differ as to what happened next. Con dashed forward to wish Larkin good luck and called for three cheers. The situation became dangerous when someone smashed one of Clery’s windows. The police said the crowd rushed them and they were pushed back before they drew batons and charged. Con remembered being struck by a policeman.

‘As I turned away an Inspector on Larkin’s right hit me on the nose and mouth with his clenched fist. I reeled against another policeman, who pulled me about, tearing all the buttons off my blouse, and tearing it out and around my waist. He then threw me back into the middle of the street, where all the police had begun to run, several of them kicking and hitting me as they passed.’

Casi later claimed he saw Con being beaten and stuffed his pipe into his pocket.

‘Another move and you’re a dead man,’ he warned the policeman who immediately backed off. Con doesn’t mention this rescue in her account, but wrote of being taken to a house in Sackville Place for medical treatment.

The crowd scattered to escape the police batons and were caught in a cordon coming across the street. The police struck out at men and women, children and old people without exception. Con caught a smell of drink from her attackers: a free bar was in operation in police stations. Many of the injured were Sunday strollers and people coming from Mass in the Pro-Cathedral.

Casi was outraged at the police brutality and went immediately to Dublin Castle where he protested to the Under Secretary, Sir James Dougherty. There was little that could be done as the police riot was over in fifteen minutes. That evening trouble broke out all over Dublin, starting in the slum areas and spreading throughout the city. The army was called out and dispersed crowds with fixed bayonets. Later that day the police copper-fastened their reputation for barbaric behaviour when they invaded a public housing complex in Corporation Street. Some were half-drunk and in plain clothes. They beat anyone they could find, including a paralysed man in his bed. They broke windows, wrecked homemade altars and threw flatdwellers’ possessions from balconies.

A woman described the scene to Nora Connolly O’Brien: ‘They came into my place and smashed every bit of delph, every picture on the wall. I was scared stiff and tried to keep out of their way. A great big country policeman jumping around the room, smashing everything his baton could touch, yelling and roaring all the time. I thought my end had come – ’

‘In some cases the police did not leave the people a cup to drink out of,’ a senior Corporation official reported at the enquiry.

The outcome on O’Connell Street may easily have been different. A contingent of Na Fianna, armed with hurleys to protect protestors, arrived in the city centre, but were diverted to a march to Clontarf. One Fianna scout who went to O’Connell Street was Patsy O’Connor who put his training into practise when he gave first aid to an injured man. He was batoned by the police and died prematurely two years later.

Up to this point Casi had avoided close identification with any faction in Ireland, but this was a breaking point. His letter in Monday’s Freeman’s Journal was a rare display of controlled indignation.

“Sir, allow me as an impartial witness, to put before you and your readers the scene of unprecedented violence which I saw today in Sackville Street at 1.30 o’clock. As a foreign press representative I went on a car to the scene of the proclaimed meeting. I found a very small crowd of people, chiefly onlookers, already there, peaceful and orderly, and a great force of police gathered both in Sackville Street and the adjoining side-streets.

I witnessed the appearance of Mr. Larkin on the balcony of the Imperial Hotel. It evoked a mild outburst of cheering from the crowd – if it may be called that. Mr. Larkin was at once arrested and taken away by a side-street. There was no sign of excitement, no attempt at rescue, and no attempted breach of the peace, when the savage and cruel order for a baton charge – unprecedented in such circumstances in any civilized country – was given to the police. It was equaled, perhaps, by the bloody Sunday events in St. Petersburg.

Scores of well-fed metropolitan policemen pursued a handful of men, women and children running for their lives before them. Round the corner of Prince’s street I saw a young man pursued by a huge policeman, knocked down by a baton stroke, and then, whilst bleeding on the ground, batoned and kicked, not only by this policemen, but by his colleagues lusting for slaughter. I saw many batoned people lying on the ground, senseless and bleeding. When the police had finished their bloodthirsty pursuit, they returned down the street batoning the terror-stricken passers-by who had taken refuge in the doorways. It was indeed a bloody Sunday for Ireland.

Photographs taken by the Press representatives will bear irrefutable testimony to the truth of my statement. I at once sought Sir James Dougherty and told him what I had witnessed. I felt it my duty also to inform the foreign Press. No human being could be silent after what I saw, and the public should insist on a sworn inquiry.

Casimir Dunin Markievicz, Surrey House, Rathmines.”

The name Bloody Sunday stuck to August 31st. About 500 people were injured and two men died as a result of injuries received from the police. It was a publicity disaster for the authorities whose reliance on brutality was exposed to the world and helped to radicalize a new generation of militants. The police claimed most injuries resulted from people who knocked each other down as they ran across the street. It was clear from now on that the authorities were on the side of the employers. The strikers were harassed at every opportunity while strike-breakers were allowed to carry guns and use them in the streets.

Larkin appeared in court on Monday, still dressed in Casi’s attire, the best-dressed figure in the dock. William Martin Murphy did not comment on his rival in that morning’s Irish Times. He was more concerned with a possible rally by Lane supporters and wrote that he had offered to pay for a ballot of ratepayers on the pictures issue, but was refused. When Hugh Lane heard of the baton charge he said: “I hope that Murphy will get a crack on the head by one of the Police soon.”

Dublin became a battleground over the next four months with regular reports of arson, riots and shootings, but Casi’s battle was with former colleagues in the Dublin Repertory Company and the Gaiety Theatre. First he had to attend to artistic matters – the annual art exhibition since 1903 went ahead as usual with AE and Francis Baker.

The rioting did not deter the Dublin Employers Federation from locking-out workers who refused to sign a pledge disowning the Transport Union and the sympathetic strike. Many who were thrown out of work had no part in the dispute as the issue became one of union recognition. Murphy succeeded in united the employers into a unit to take the short-term loss in hope of eventual gain. He convinced them that if Connolly and Larkin succeeded in implementing the Syndicalist programme it would be the end of the Guinnesses, the Easons and the other business families of Dublin. Their businesses would be expropriated by the union where one man in theory had the same power as another. And what is wealth but a particular form of power?

The Transport Union appealed for help from the unions in Britain and ship-loads of food began to appear on the docks. On 6 September two buildings collapsed in Church Street and killed seven people. The Corporation had another crisis to deal with. The Corporation decided that the Liffey site was unsuitable and urged Lane to leave the choice of site and architect to them. The Dublin Saturday Herald announced an inquest into the remains of the Gallery project. Yeats was furious and elevated what had been a shopkeeper’s convenience into a symbol of modern Ireland:

“What need you, being come to sense,

But fumble in a greasy till

And add the halfpence to the pence

And prayer to shivering prayer, until

You have dried the marrow from the bone;

For men were born to pray and save:

Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone,

It’s with O’Leary in the grave.”

Lane packed up the pictures and announced he had found a venue that would appreciate them. They were going to Belfast.

During the last four months of 1913 Con was fully occupied in political work – she spoke at women’s suffrage meetings, kept up activities in the Fianna, but most of all she was absorbed in helping people most affected by the strike. Connolly was in charge of food supplies and he left most of the effort to Con and Larkin’s sister, Delia. They organized food for strikers and their families with a food kitchen in Liberty Hall. Con was in charge of the Women and Children’s Relief Fund and received payments from the British TUC in this regard. Two girls who had been made homeless after being locked out by Jacobs Biscuit factory were put up in Surrey House.

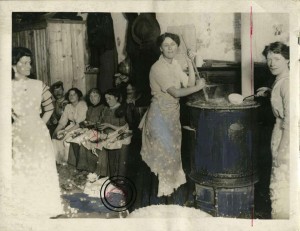

A visitor from The Irish Citizen described the kitchen in Liberty Hall:

‘Here under the capable supervision of Madame Markievicz, about a score of girls, are at work peeling potatoes and cutting up meat. They are all intelligent, they are all keen, they are all tidy, and they are all locked-out. Some half-dozen men are also busy – stoking the fire under the huge cauldron, fetching water and bringing from the store-room great stacks of bread.’

Liberty Hall was open every day during the Lock-out. Con discovered that many women were going hungry to feed their families. She insisted on setting up a special dining area for mothers. She gave all her energy to the work in Liberty Hall and stories of her generosity abounded. Many of those locked-out were girls from Jacobs who later became activists in Cumann na mBan. The British trade union leader, Harry Gosling, described her as working all day with sleeves rolled up, a sack for an apron and a cigarette in her mouth. Dubliners said there was a man on standby to go to her solicitors and get money from her shrinking marriage settlement from the Gore-Booth estate.

Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington told of a boy in the queue for food whose father had taken the job of a worker. The children taunted him, but Con came to his defence and said it wasn’t the child’s fault if his father was a scab. She allowed him to stay for soup like the rest.

Con’s work in 1913 endeared her to the Dublin poor as much as her later political work. It ensured a massive turnout at her funeral in 1927 and an enduring affection in folk memory. When the strike was over the ITGWU presented her with an illustrated scroll and made her an honorary member: “…you came to our aid to organize relief, and for months worked amongst us, and served the cause of labour by such untiring toil, far seeing vigilance and sympathetic insight as cheered and encouraged all who were privileged to witness it…”

During the Lockout she moved from being a marginal figure to a more central role. Her work in Liberty Hall turned her into an iconic figure in Dublin. She found her vocation in the long hours in Liberty Hall. She knew she was different from the people. She could never lose her high-pitched Anglo-Irish accent or her aristocratic air of a born leader, but she could roll up her sleeves and work alongside the volunteers from the Irish Women Workers Union. By the year’s end she was Treasurer of the Irish Citizen Army and in the confidence of the leaders of the Irish Volunteers. She was as well on her way to becoming an actor on the national stage.

James Connolly went on hunger strike against his imprisonment. After a week the Government released him and Lord Aberdeen sent his personal car to take him from prison to Surrey House where he became a lodger until going back to work in Belfast. Con continued to support the Irish Women’s Franchise League and spoke at a meeting outside Liberty Hall in September. The Irish Citizen (27/09/13) reported:

‘Constance Markievicz, who followed, and whose appearance was greeted with applause, spoke of the moral and educational value of the vote, and what a large factor it was in the mental growth and social development of the men in the community. She declared there were three great movements going on in Ireland at present – the National Movement, the Women’s Movement, and the Industrial movement. They were all really the same movements in essence, for they were all fighting the same fight, for the extension of human liberty.’

Con was involved, albeit indirectly, with the plan to remove children to homes in England for a holiday. The scheme was the brainchild of British feminist, Dora Montefiore and drew down the ire of the Catholic Church and the Ancient Order of Hibernians. Catholic priests led mobs to railway stations and attacked Montefiore’s helpers.

The scheme collapsed and the ladies found themselves in prison on kidnapping charges. Con raised the bail money for the release of Montefiore and Lucille Rand. The Irish Citizen noted a first for a woman to be accepted for bail.

The dispute led to bitterness between the church and the Ancient Order of Hibernians on one side and socialists and libertarians on the other. A leaflet from the time chooses Con as a target for Catholic nationalists:

‘Belfast Catholics should ask Madame Markievicz what part she played in Dublin at the time of the deportation of the poor Catholic Children when Larkinism and Liberty Hall tactics brought the working class to the verge of starvation!’

The bitter experience of the lock-out led to a convergence among socialists, physical-force nationalists, suffragettes and libertarians that would lead to the rebellion in 1916.

The Gaiety Theatre demanded that the Dublin Repertory Company remove Con from a forthcoming production of Eleanor’s Enterprise, arguing that her appearance on stage would be bad for business. The Gaiety Board was reluctant to antagonize Murphy. Casi published the correspondence between himself, the Gaiety and Ashley in the Irish Times. David Telford led the charge for the Gaiety when he wrote to Ashley:

“if she insists on playing, a number of other artists will refuse to play. Under these circumstances what do you suggest should be done? If the Count and you consent I would prefer to cancel the outstanding dates, but if you not agree to that you must produce such plays as I approve of. I must confess I strongly disapprove of Eleanor’s Enterprise in present circumstances, but the Count has pressed me so hard that I very reluctantly told him that, if he obtained your consent to the Countess playing, I might reconsider the matter.”

Ashley declared his opposition to his kinswoman in implacable terms. He agreed with Telford that Eleanor’s Enterprise should not go on and said he had made this clear to the Count and Countess: “– if the Count cannot see that his attitude and that of his wife is only calculated to do the Repertory Theatre movement irreparable injury, then I suggest the sooner he sever all connection with it the better. I shall make arrangements for the production of other plays for November and December.”

It was a bitter reaction from one who worked so closely with Casi and shows the gulf between those who questioned and those who upheld the status quo. Whatever his feelings about Larkin and the strike Casi had no intention of sacrificing Con to suit the Gaiety. He replied to Telford on 13 October: “Dear Sir, since our interview of the 14th inst, I have been considering my position as joint manager of the Dublin Repertory Theatre Company, and in view of the attitude adopted by Mr Ashley and you with reference to your refusal to allow the production of Eleanor’s Enterprise, as arranged if Countess Markievicz is to play a part, I see no course open to me save to retire from the joint management of the Repertory Company.

Please cancel any engagements made by me, and understand that I can no longer be responsible in any way for the company. I am sending copies of all correspondence to the press. Yours Faithfully, Dunin-Markievicz.”

The last letter was addressed to Ashley: “As I am convinced that your policy must be fatal to the interest of the Repertory Theatre movement, as well as insulting to the people of this city, I feel it is impossible for me to retain my position as co-director of the Dublin Repertory Theatre Company.”

It must have been galling for Casi to have close collaborators turn against him. His links with the Irish theatre world were effectively cut. It was the end of an adventurous era in popular theatre. For the last five years he and Con been a major influence in Dublin – they set up companies, acted and directed, wrote plays and stage-managed others. They were a dynamic couple and they broadened the Irish dramatic repertoire and were innovative in production values and choice of plays. The couple’s contribution to Irish drama, has been judged significant by a modern writer:

“They had given financial support to the Irish Literary Theatre and to the Theatre of Ireland, and broadened the Irish dramatic repertoire with their involvement in the amateur companies. They also found innovative ways to interest spectators in modernist drama. The scope and variety of the Markieviczes’ performances illustrates their awareness of the wide-ranging opportunities in modern drama as well as their attentiveness to what ordinary people expected from the theatre.”

Winter

Larkin was released from prison on 13 November after 17 days inside. At a meeting to celebrate his release a massive demonstration was held in Dublin at which Connolly called for a worker’s militia:

‘The next time we go out for a march I want to be accompanied by four battalions of our own men. I want them to have their own corporals and sergeants and men who will be able to ‘form fours.’ Why should we not drill men as well as in Ulster?’

It was the first public announcement of what was to become The Irish Citizen Army. In the beginning it was conceived as a protective force armed with hurley sticks against police attacks, but developed into a military force that took part in the rebellion of 1916. Con also spoke about ‘the proudest moment of my life, to be associated with the workers of Dublin when their great and noble leader has been released.’

“I think Larkin will beat Murphy yet,” Hugh Lane wrote. “I hope so.”

According to Kevin Myers, Casi was “the unfortunate Polish husband, who soon fled her neurotic badness for the security of war on the eastern front.” This interpretation has become the popular version of events. The Arts Club historian, Patricia Boylan, wrote that: “the Dublin of violence and strikes and his wife’s involvement in them alienated the ‘royal tramp’ and he finally left Ireland for the Ukraine.”

Despite Con’s concerns when she was leasing Surrey House that Casi would have space to work he does not appear to have been happy or productive there. O’Faolain mentions an incident when a Citizen Army man made a disparaging remark about people with titles. Casi caught him by the collar and belt and swung him around before throwing him through the window. The people in the room fell into silence at this uncharacteristic show of force.

“So!” Casi exclaimed as he wiped his hands.

Con dissolved the tension with a laugh. The incident suggests a volcanic simmering beneath the calm exterior.

‘Sometimes she would get bored with him,’ Helena Molony said. ”You are so tiresome,” she would say. Neither of them would, at any time, had the slightest intention of separating. She was quite content to have him in Poland, and quite content to have him here…He lapped it up.’

Surrey House was now full of people coming and going day and night. Most of the visitors were different from the carefree bohemian crowd who loved the gaiety surrounding the theatre. Casi was on good terms with Thomas MacDonough, the poet and 1916 leader. MacDonough bought the melancholy Ukrainian landscape and printed it along with The Fencing Master and Portrait of AE in his journal, The Irish Review. The majority of Con’s visitors were deeply involved in Irish revolutionary politics – a topic Casi found interesting, but not absorbing.

Con had plenty of critics who blamed her for driving the good companion away. In Surrey House he would debate with the zealots before leaving for town and more congenial company. When he returned he could be greeted by a “sprout” demanding a password. If he entered the drawing- room unexpectedly he might interrupt a committee meeting and retreat with apologies. There was no room in the house to paint – all space was taken up with revolutionary activities. To make matters worse the house and its occupants were under constant surveillance by the police.

What did he do between September and December? It was unusual period in his life. For the past ten years the autumn months had been a flurry of painting, writing and theatre performances. I can’t imagine him cooling his heels on cold evenings outside Beresford Place listening to long-winded speeches denouncing employers and scabs. The United Arts Club was a congenial refuge where he could meet his old friends. The atmosphere in the pubs had become sour. Rather than being a source of entertainment the Count was becoming a figure of fun and he realised that malice often lies beneath a smile. Jokes began to circulate which pretended to confuse the Vice-Regal Lodge with Liberty Hall. Lord Aberdeen complimented Con on her soup while Casi helped Lady Aberdeen with her public health campaigns. It was a relief to find any corner where he could work on his Polish play, The Wild Field, and make plans for the journey to the Balkans.

There is no evidence that he intended to leave Ireland for good. If that was his intention it didn’t make sense to leave his best pictures – Bread, Amour, Constance in White as well as a portrait of his first wife, Jadwiga. He left the greater part of his wardrobe in Surrey House. With the drying-up of commissions and the end of his theatre ventures he had to look for other ways to earn a living. He had a valuable connection with the impresario Arnold Szyfman who was establishing Polish theatre in Kiev. Casi had invaluable experience of all aspects of theatre from his Dublin years.

Casi told a story about their “summer residence,” which could only have been the cottage in Balally. Con was out late at a meeting and he was alone in bed. After a while he began to feel uncomfortable. He got up and looked under the mattress. To his amazement he saw wooden boxes crammed with bombs and dynamite. “So I left Poland to get married to an English aristocrat. Did I think I would find myself a few years later sleeping alone on dynamite?”

He claimed the episode put him into a bad mood. He didn’t care about Ireland. “It should go to hell!” O’Faolain quotes an appeal from the heart: “Is there no one to appear in a burning bush to save me? She offer me to Ireland as a sacrifice.” It’s doubtful if he said this; his English was much better in 1913

Con was still interested in the theatre to be prepared to appear in Eleanor’s Enterprise, but the break with the Dublin Repertory Theatre which she had supported so enthusiastically meant the end of theatre for her until she used it for propaganda work in the 1920s.

Was there a scene in Surrey House or in Balally where he declared he had enough of Ireland? Did he say he was going to concentrate on work in Kiev and Warsaw in future? For such a public couple they were private about intimate issues. I think they talked not about the growing gap between them, but about the need to earn money and how it would be easier in Kiev. I think they were tender and careful with each other’s feelings. There’s a zone between reality and possibility where hope can flourish. Neither would accept that it might be a permanent break. I can see them together:

Casi: Con, I can do no work in Dublin. I must leave.

Con: But this is your home.

Casi: I will be back. Things will settle down in a while.

Con: It won’t be the same without you.

Casi: You are so busy you won’t even miss me.

Con: My darling, I’ll always miss you.

He holds her in his arms and as he looks into her tear-filled eyes he sees the beauty he held in Paris with her brown hair falling over her bare shoulders. He begins to weaken. And then someone knocks at the door and calls:

‘Madame, you’re wanted urgently in Liberty Hall.’

And the fragile moment is broken. Never to be repeated, except maybe on his return eleven years later.

Everyone knew that this leave-taking was different from his usual departure. Lennox Robinson was at a farewell reception in the Abbey’s Green Room – he said he never saw Con as sad as on that occasion.

The Evening Herald gave him a front-page headline: “The Count Leaves his Dublin Home.”

Tommy Furlong organized the farewell party for Casimir on 6 December. His friends came to an American Wake, complete with snuff and candles. The party was held in Fuller’s of Grafton Street, once a Dublin favourite along with Bewley’s and Jammets. Seumas O’Sullivan suggested that some of the colour of the city would disappear with Casi’s departure. Gogarty continued the tradition of celebration with a sonnet in his friend’s honour:

Kasimir, the name that clashes like a sword

Through skulls of dullards and brings back old Joy!

Kasimir, you great incorrigible boy!

A Centaur, laughing on a mountain sward

Could just as little with our life accord

As you can with the little peoples here.

A thing of brain and beauty, stallion and seer,

Like him who taught the Trojans overlord.

We cringe in Art and Ethics. You’re above

Our best in Painting, Poetry and Love:

And this the faint hearts by their envy prove,

Thus: Dublin getting as they all aver

More than a Poland for its Oliver

When you came out of Poland, Kazimir.

The Reality League did not survive Casi’s departure, but the friendships continued through revolution and war into the uncertain years of the Irish Free State. Gogarty became a Senator along with Yeats; Montgomery had the dubious honour of becoming the first official Film Censor. And O’Sullivan developed as a poet of intense moods who made the Dublin Magazine an outlet for Irish and international writers. But when Casimir returned to Dublin in 1924 he found a city of little joy and barely a memory of the Reality League.

William Martin Murphy emerged the winner from the carnage of 1913. He was quite modest about his victory over Lane and Larkin. But he lost the moral victory and has been condemned, if not to manage an art gallery in Hell, to wander through eternity to the music of jingling halfpence in the greasy till.

Con identified herself from now on with the socialist cause which led to her becoming the first woman Minister for Labour. She created links between the different social forces and their organizations. She threw herself into the battle in 1913 and endured the pains of defeat. She suffered for a losing side, which is, in the words of Cecil Day Lewis, ‘the side which always at last is seen to have won.’

Casi was a man of two countries; he loved Ireland and he loved Poland. He had many adventures after he left Ireland in 1913, but kept up an interest in the country. He wrote a pamphlet on Ireland in Russia during the Revolution. He surely had Con in mind when he wrote of Irishwomen having “wide open faces with beautiful eyes and turbulent hair.” Later in Poland he wrote letters, journalism and a novel set in Ireland. One of his last letters was to his sister-in-law, Molly Gore-Booth. Ireland was a deep and enduring part of his life and his romance with the country did not end with the events of 1913.

(C) Patrick Quigley 2013