Was Labour Ever Ready for Power?

1913 and Beyond

‘Fellow delegates, In presenting their report for the year just passed your Committee have again to express their regret that labour legislation is not advanced during the period under review to any appreciable extent, and to record a succession of serious disappointments is but to place before you the absolute truth’.

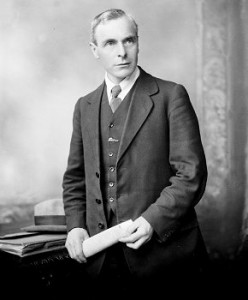

Thus Tom Johnson, with characteristic modesty and truth, opened the 1914 conference of the Irish Trade Union Congress on the Whit Monday of that year in Dublin City Hall. (The ‘and Labour Party’ suffix had yet to be added to the title page). It was a theme sadly familiar to participants, made all the more galling by the continuing close relationship between John Redmond’s Irish Parliamentary Party and the British Labour Party. The most important ‘disappointment’ had been the failure to have the National Health Insurance Act extended to Ireland. Even more galling was the decision of the British Labour Party in the aftermath of the Lockout to facilitate P J Brady, the Irish Party MP for the Stephen’s Green Division of Dublin City, in presenting a Bill to extend the Feeding of the Necessitous School Children’s Act to Ireland. Not only was the measure more restrictive than the English legislation but it allowed the Redmondites to claim credit for a measure repeatedly demanded by the ITUC and Irish female suffrage groups, which the IPP had previously opposed.

When Jim Larkin was elected President of the ITUC by acclamation that morning he did no more than voice the frustration of the whole assembly when he attacked the British Labour Party for ‘taking counsel with the Irish National Party on labour matters or on questions affecting the workers in Ireland over the heads of the representatives of the Irish Trade Union Congress’; especially as ‘these were the very men … whom in Ireland they had to fight as amongst their bitterest enemies’. Larkin had first made his protest at this policy the previous July, when he was part of the ITUC Parliamentary Committee delegation that met Labour MPs in the House of Commons.

It does not appear to have been a very fruitful meeting. Arthur Henderson conceded more could be done on some fronts, such as stricter enforcement of the Factory Acts, but counter attacked with an assertion that the ITUC had failed to forward amendments it wanted to the Home Rule Bill. P T Daly pointed out that Augustine Birrell, the Chief Secretary, had announced he was taking no more amendments to the Bill as part of his effort to close off debate before Ulster Unionists could mobilise support to sabotage the measure completely.

Things were no better when both sides met again in Dublin on September 6th, 1913, the day before the mass rally in O’Connell Street at which Labour and Lib-Lab MPs joined with ITUC speakers in castigating the employers of Dublin and vindicating the rights of workers to freedom of assembly and free speech a week after Bloody Sunday. If anything the discussions showed that even at this critical moment, three days after the Dublin Chamber of Commerce had declared a Lockout, solidarity was a scarce commodity between British and Irish labour. As is often the case in family disputes, it all boiled down to who had custody of the money. The Irish unions wanted to ensure that at least some of the political levy paid by Irish members of British based unions should be refunded to build the new Irish Labour Party. Once again Henderson took the lead and told them bluntly that he could not see TUC affiliates agreeing to fund a party concerned exclusively with Irish affairs, to which William O’Brien and D R Campbell responded that they would continue to work with British labour ‘on broader matters, while retaining local autonomy’. Campbell added that Irish resolutions ‘were always relegated to the end of the agenda at British congresses and conferences’. He explained bluntly that, ‘The idea was that the Irish Labour Party should be responsible to the Irish Congress’.

In many ways the dispute between the British TUC and the ITUC mirrored those between the parties to the wider Home Rule debate. Like many Irish Unionists, Irish trade unionists had a schizophrenic approach to Home Rule and the emerging challenge of Partition. Nobody wanted Partition but neither could the conflicting parties agree to capitulate on the alternatives – Home Rule for all or an indefinite continuation of the Union. It was bedevilled by two further issues that divided British and Irish labour.

One was the British Labour Party’s acceptance of the new constituencies for the Home Rule parliament, which seriously undermined the prospects of Irish Labour winning any seats. Existing constituencies based on large urban centres such as Newry, Kilkenny, Wexford and Galway were to be split and attached to larger rural areas. ITUC hopes that larger cities such as Belfast and Dublin would be single multi-seat constituencies were also dashed. For instance instead of Belfast being a one 14 seat constituency, it would have the 14 seats divided between four constituencies, making it harder not alone for Labour to maximise the working class vote but easier for Unionist and nationalist opponents to perpetuate sectarian divisions. In Dublin city the ITUC had also been hoping for a single 14 seat constituency with a single three seat constituency in the county. Instead the Home Rule Bill made provision for only 11 seats spread across four constituencies in the city while County Dublin was allocated six seats spread across two constituencies. Nationally there would be only 34 urban based constituencies as opposed to 128 rural based constituencies.

The second issue was a fundamental ideological division that had emerged. British labour was a broad beamed vessel accommodating trade unionists, socialist organisations and the Co-Operative movement. Irish labour was exclusively centred on the trade unions. Even radicals such as James Connolly accepted the realpolitik that the Irish Labour Party would have to grow out of the TUC in the hope that this would gradually become more radical. Many ITUC members were actively hostile to socialism. Another problem was that the Co-Operative movement in Ireland was very different to Britain. It was rural based, rather than urban based and it was producer oriented rather than consumer oriented. The Irish movement was dominated by farmers rather than enthusiasts to create the Webb’s vision of a ‘Commonwealth of Consumers’ to combine with the ‘Commonwealth of Producers’ which would replace capitalism relatively painlessly. Figures as diverse as David Campbell and Michael O’Lehane were united in their opposition to involving the Co-Operatives. Campbell, a close ally of Connolly in Belfast, pointed out that ‘some people’ in the Co-Operative movement ‘had a hereditary opposition to trade unionism’. Sinn Feiner, O’Lehane agreed and added that, ‘If Co-ops and socialist bodies were admitted they could not keep out other labour organisations; and some organisations of agricultural labourers might come in’. There was a deep distrust of land and labour leagues that might provide Redmondites with a back door to take over the ITUC.

Opposition to extending the movement outside the trade union family even came from L Lumley of the Amalgamated Union of Co-Operative Employees. He said that some Co-Operative societies ‘were controlled by dividend hunters who were nothing better than capitalists’ while John Drummond of another British ‘amalgamated’ the ‘Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen’ declared that a purely trade union organisation ‘would prevent bounders on the hop coming in as MPs’. His target, and that of many speakers, including Larkin, who said ‘A man who was not a Trade Unionist was not a Socialist’, was Ramsay MacDonald, one of the British MPs most antipathetic to the Irish cause. (It was ironic given Larkin’s defence of Countess Mackievicz’ s membership of the Irish Citizen Army a few months later, although she was not a trade unionist. But then erraticism is the one consistent of his career.)

As usual Tom Johnson summed up the state of mind of the ITUC best. While expressing some sympathy for the English approach to building a movement, he said that in Ireland it was ‘desirable simply to extend the facilities of the TUC to include political action. The true function of the Socialist bodies was propagandist merely – to educate, not to form a political party. The Irish Labour Party should be based on the industrial working class in its organised capacity’. Another irony of the situation was that the Socialist Party of Ireland and, more particularly the Independent Labour Party, which contained many of the leading Irish radical socialists of the day would be excluded from the new organisation.

Of course these discussions were taking place against the backdrop of the Lockout that certainly put the organised capacity of the industrial working class to the test. After all the central issue at stake was collective bargaining, which was as bitterly contested by employers then as it is now. The difference, and it was a significant one, was that the prospect of Home Rule made the future looked a lot brighter in 1913. Despite their criticisms of the Home Rule Bill many Irish trade unionists saw greater national freedom and liberation from economic servitude as complementary rather than mutually incompatible goals. At a more fundamental level Larkin and other labour leaders clearly understood that without collective bargaining the power of their movement in a Home Rule Ireland would be seriously weakened. But, paradoxically, such was the power of nationalism in the early twentieth century, that this did not dim their optimism of a brighter future in an overwhelmingly rural based society. Unfortunately men such as William Martin Murphy and John Dillon, who well remembered the Land Wars, also understood the power of collective action very well. Ironically Dillon would be unveiling a memorial to two martyrs of the Land League in Mayo on Bloody Sunday 1913, when the incompetence and brutality of the DMP and RIC let the syndicalist genie out of the bottle in Dublin.

No one could ever accuse Larkin of being afraid of a fight and if he was reluctant to engage in strike action at the DUTC in the summer of 1913, as he was at the Guinness Brewery, it was because he knew the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union was not ready for it. Whether he sensed that Murphy would use it as a casus belli to unleash the Lockout we do not know. There were certainly straws in the wind, such as the pre-emptive move by Shackleton’s and Wookeys’ mills in west county Dublin and by Jacob’s Biscuits in the city, who locked out ITGWU members before the Chamber of Commerce and the Dublin Employers Federation decided to formally endorse the lockout tactic. Their actions indicated a new hawkishness was abroad in the employers’ ranks at odds with the conciliation and mediation plan proposed by Lorcan Sherlock, the Lord Mayor of Dublin, that summer. We tend to forget that the establishment of a city wide conciliation scheme, which would have prevented a lockout, was only a fortnight away when the tram strike began.

It is probable that Murphy would have purged his own enterprises of the ITGWU anyway and that some employers in the city would have followed suit. However, if they had acted without the provocation of the tram strike and with a conciliation and arbitration scheme imminent they would have been going against the prevailing mood in the city. It is possible that many of the 400 firms who backed Murphy in September would have baulked at adopting such an extreme measure as a lockout of ITGWU members, let alone agreeing to a de facto extension of the measure to other unions in more settled conditions.

It was inevitable that differences between the TUC and the ITUC would surface during the dispute, especially as the reality of defeat dawned. Long before the refusal of the TUC special delegate conference of December 9th to extend official sympathetic action to Britain, Dublin was isolated in the minds of the TUC leadership because of fundamentally different approaches towards building a labour movement. Larkin’s reckless attacks on the TUC leadership simply aggravated this an highlighted the generation gap between the Dublin strike leaders intoxicated with syndicalism and the older TUC leaders who had grown old fighting for the basic right to organise. The latter knew the harsh realities of strikes and lockouts even better than the Dublin firebrands. They knew that the threat of sympathetic strike action could be a useful thing against a weak and inexperienced employer, or in comparatively rare situations but they also knew that it often boomeranged on the wielder. Contemporary Board of Trade figures showed that, while trade unions were completely successful in 31 per cent of sectional disputes and partially successful in another 48 per cent, only five per cent of sympathetic strikes ended in victory for the workers.

The problem, as Larkin’s supporters in Britain quickly discovered, was that refusing to handle tainted goods from Dublin degenerated within 24 to 48 hours into disputes about reinstating the men concerned, who had usually been suspended or sacked. The truth was that syndicalism, industrial unionism, ‘Larkinism’, or any strategy that rested so heavily on the power of organised labour was doomed to defeat. William Martin Murphy won not just because the employers had deeper pockets but because he had the support of Dublin Castle, the courts, the bulk of the clergy from the Catholic and Protestant churches, the tacit support of those stanch allies of British labour, the Redmondites and rural Ireland on his side. His domination of the Irish media allowed him to mould Irish middle class opinion while secret agreements ensured financial subsidies and practical aid from British employers. Larkin was right in depicting Murphy as a ‘financial octopus’ in the Irish Worker, the problem was that the Larkinites’ almost total dependence on industrial muscle meant that they were fighting with one arm tied behind their backs. Not an ideal stance in a contest with an octopus.

I am not suggesting they had much choice. In fact it makes the fight they put up all the more remarkable and admirable. The background of conflict on the political front with the TUC also makes their allegations of a ‘stab in the back’ more understandable, if it does not validate them. With the best will in the world, which was clearly absent, the TUC lacked both the organisational power and the political capacity to win Dublin’s battles for it. They were simply outmatched. The figures speak for themselves. During the Lockout and its immediate aftermath over £93,000 was spent directly in supporting the Dublin Trades Council. Over the same period lost wages in working class districts of the city were estimated at £400,000. We have no detailed figures for business lost in Dublin but experienced commentators estimated the overall cost at £300,000 a week at the conflict’s peak. The overall cost may have been £2.3 million, including the £400,000 in lost wages. But this was widely spread and, as Murphy was able to remind workers, employers could still afford three square meals a day. The revenue of the Dublin Port and Docks Board, one of the enterprises most affected by the dispute only fell from £94,128 in 1912 to £86,215 in 1913, a drop of 8.4 per cent. The DUTC, the company at its epicentre, saw net profits fall from £142,382 to £119,871 over the same period, resulting in a cut of half a per cent in the annual dividend on ordinary shares. By contrast the six days of the Easter Rising cost the city an estimated £2.5 million in damage to property, a lot of it owned by William Martin Murphy. The cost of the Lockout to those subsidising the Dublin employers over the same period, such as the British Shipping Federation, the Engineering Federation and Lord Iveagh was less than £20,000. In other words subsidising class war in Dublin cost the TUC £5 for every one pound spent by the enemy. (Some commentators put the overall value of support to the DTC at £150,000.) The secret subsidies may well have been vital in keeping some Dublin employers from settling, at least that is what Murphy told Guinness management. The Shipping Federation also supplied ‘scabs’ or ‘free labourers’, and much of the expertise needed to break the strike. As we have seen, the employers could also call on the not inconsiderable resources of the British state; although the Chief Secretary, Augustine Birrell, drew the line at deploying gunboats on the Liffey, as demanded by some.

All Larkin could hope for, and sought, was an honourable truce. Unfortunately Murphy was only interested in a ‘Carthaginian peace’ and that is what he succeeded in imposing. It was left to the Dublin trade union leaders to advise their members to return to work on what terms they could obtain. Some employers, such as the Dublin Port and Docks Board, did not require their men to sign the declaration renouncing the ITGWU and generally speaking did not cut wages. Others, such as the Dublin Master Builders Association, not only insisted on men signing the document renouncing the ITGWU, but required an undertaking from other unions to expel members who refused to sign the document. Jacob’s went one further and refused to take back many strikers on any conditions, including about 400 women.

The ITGWU membership survived the Lockout remarkably well, only falling from 30,000 in August 1913 to 26,000 in December. But the decline continued (possibly accelerated by Larkin’s departure to America) to 15,000 in 1914 and 10,000 in 1915. By 1916 membership was a mere 5,000. The revival that followed the Easter Rising undoubtedly owed much to Connolly’s martyrdom, but even more to the tenacity of ITGWU General President Tom Foran, other executive members and the organising genius of William O’Brien. The introduction of the British Committee on Production system of arbitration during the war, which allowed for de facto union recognition was another major factor in the recovery of the trade union movement. Although restricted to war industries the arbitration system set benchmarks for the wider labour market. Labour shortages also contributed to the growing mood of confidence and militancy among Irish workers, but it is important not to ignore the significance of the structural props provided by the state. Would that we had them today.

While the association of the ITGWU and labour movement in general with the struggle for independence was mutually beneficial, we should not forget that the subordinate role reflected labour’s political underdevelopment. On paper it was much stronger organisationally than Sinn Fein, particularly in Dublin and Belfast, even if it was divided on the issue of self-determination. What made the movement particularly susceptible to outside political forces was the fact that it was primarily an extension of the local trades’ councils. This was made quite explicit in the rules adopted at the ITUC conference in 1914. In fact the only way to obtain a Labour nomination was through a trades council or, in its absence, through the ITUC national executive.

A great deal more research is needed by local historians on the state of labour and, by extension, trades councils throughout Ireland, before we can explain adequately its political failure, not alone in 1918 but subsequently. The lack of a coherent core ideology and policies based on that ideology surely played their part in denying labour a leading role in the struggle for independence in the south. On the other hand, perhaps the lack of such policies to differentiate it from other parties actually facilitated Labour’s relatively respectable electoral performance in many places. After all, in Dublin, where the party was more radical than elsewhere it only secured 12 per cent of the first preference vote in the municipal elections of 1920, compared with a national average of 18 per cent and 19 per cent in Belfast. This was partly because the movement in the capital was badly split between the rival O’Brienite and Dalyite wings, a split that was formalised by the establishment of two rival trades councils and electoral slates. But perhaps it was also because the message of neither wing resonated well with the electorate. Perhaps Labour was too radical in Dublin and Sinn Fein was already developing the ‘catch-all’ approach that would serve Fine Gael and Fianna Fail so well in the future.

The alliance that emerged between organised labour, female suffrage campaigners and radical nationalists in the city during the Lockout would endure for most of the following decade. It added an important radical dimension to the struggle for independence, without which such decisive battles as the anti-conscription campaign and munitions strike could not have been won, but these radical forces were only successful so long as their activities were compatible with the broader, underlying neo-Redmondite nationalist consensus that outlived the Irish Party. Whether independence served the long term interests of working class men and women is more debatable. Arguably they would have been better off remaining within an urbanised, liberal minded, middle class democracy such as Britain. Of course hundreds of thousands of the working poor voted with their feet. People did not leave any other country in Europe, even those enduring revolution and war, at rates remotely resembling those fleeing the Free State.

Perhaps I will leave the last word to one of the twentieth century’s great revisionists, Karl Kautsky, who wrote in 1922 that:

‘The deciding battles for Ireland’s independence in recent years were won mainly because of the energy and devotion of her proletariat. And in spite of this, this proletariat is threatened by the independent state which it won, not with an improvement, but with a further decline of its position… In an oppressed country the class contradictions are only too easily hidden and obscured by national contradictions.’

© Padraig Yeates