The Lepracaun Cartoons for 1913-14 now on view at Dublin City Libraries site

The Lepracaun Cartoon Monthly and the 1913-1914 lockout Image Gallery

‘Capital is the child of Labour. Therefore the nipper’s present paroxysm of filial piety in Dublin is not so astonishing.’

Lepracaun Cartoon Monthly, November 1913.

‘Sometimes all we need to brighten our day is to rise a little higher. In wages.’

Lepracaun Cartoon Monthly, January 1914.

The Dublin-based Lepracaun Cartoon Monthly was launched in May 1905 by Thomas Fitzpatrick, one of Ireland’s foremost cartoonists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Eclipsing in its lifespan all previous Irish comic periodicals, the Lepracaun would run for almost a decade. This meant that the publication was in a position to offer a vivid cartoon chronology of the great 1913-14 Dublin strike and lockout, although there would be no contribution from the Lepracaun’s founder and most prolific cartoonist, with the Cork-born Thomas Fitzpatrick having passed away in July 1912 at the age of 52.

The two figures most associated with the lockout, however, did attract Fitzpatrick’s notice in the Lepracaun some years earlier. In December 1908 William Martin Murphy’s career was covered by the Lepracaun in an instalment of its full-page “City Celebrities” series, with the profile marvelling at Murphy’s vast range of business concerns. Fitzpatrick’s accompanying cartoon depicted his fellow Cork-man as a great conjurer plucking newspapers, railways, trams and a hotel out of an ‘inexhaustible’ finance hat. After speculating that there might actually be ‘a few limited companies in Dublin’ of which he was not a director, the satirical profile concluded by voicing a suspicion that Murphy’s sole regret in life was the ‘melancholy reflection’ that when he eventually passed away, ‘the Chancellor of the Exchequer will congratulate himself on the acquisition of the death duties of an Irish millionaire.

As chance would have it, Murphy’s great antagonist in 1913 was referenced by Fitzpatrick in the same issue of the Lepracaun. A half-page cartoon saw him earnestly hope that ‘Mr. Jim Larkin (a good name for a labour leader)’ would use his growing influence to ensure that Dublin hearse drivers did not become caught up in a carters strike. This would help avoid the potentially ‘appalling calamity’ of their jobs being carried out under police escort by strike-breaking replacements. This was no evidence of an innate aversion to strikes, for in the Lepracaun’s next issue Fitzpatrick unequivocally declared his support for the carters, wishing them ‘every success against the money-grabbers’, whom he portrayed in a cartoon as caring more about the welfare of their horses than the starving men they paid a pittance to drive them. In a separate cartoon from the same issue Fitzpatrick also found humour in the fact that clerks ordinarily employed in the ‘Sweatem’ company’s offices were being forced to endure the humiliating ordeal of becoming temporary dray drivers under police protection. Throughout his life Fitzpatrick was noted for the social conscience which he frequently exhibited in his work, with one obituary ending with the words, ‘He took down the mighty from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly’.

Following Fitzpatrick’s death the Dublin lockout would be the subject of Lepracaun cartoons by his Cork-born friend and former mentor John Fergus O’Hea, who reacted to Fitzpatrick’s deteriorating health in 1911 by stepping in to ensure that the publication survived. In October 1911 O’Hea had depicted a Dublin bakers’ strike involving the ITGWU as a case of ‘man’s inhumanity to man’, drawing attention to the widespread suffering caused by the ‘bread famine’ and resultant rise in the price of butter. The previous month O’Hea had continued with Fitzpatrick’s long tradition of castigating the Dublin police, depicting a DMP constable leading a brutal batoning of O’Connell Street crowds while Lord Nelson danced atop his thoroughfare pillar. The message was that only policemen rather than mere members of the public had the right to ‘strike’ in Dublin.

Attacks on the DMP continued apace. In its January 1914 issue the Lepracaun rightly held out little hope that an inquiry into the “Bloody Sunday” riot and other police-related violence from during the opening days of the lockout would result in anything other than a verdict that the police used ‘legitimate pressure to end the labour trouble’. The following month saw a profile of DMP Chief Commissioner Sir John Ross include reference to how, on 30-31 August the previous year, he had heroically ‘personally supervised O’Connell Street and other city thoroughfares in which several hundred citizens were converted into Post-Impressionist pictures by his baton artists’.

This takes us back to the Lepracaun’s October 1913 issue, and the editorial comment that it had taken the recent deaths of two workers, and ‘conversion of some four hundred odd men, women and children into hospital cases, in order to give the outside world an idea of the treasure Dublin possesses in its eightpence-in-the-pound Metropolitan Police Force as protectors of the lives and liberties of the citizens’. To this was added the observation that ‘the R.I.C. ably assisted our local heroes in the baton demonstrations of August 30 and 31’. One suspects that the person behind these words was O’Hea, bearing as they did a strong resemblance to the sentiments expressed in his vivid “Real Strikers” cartoon which appeared in the Lepracaun’s same issue.

More humorous and less editorially neutral cartoons regarding the lockout appeared in the Lepracaun by “S.H.Y.”, who according to signatures attached to some of his work deposited in the National Library of Ireland was London artist Frank Reynolds. During the dispute “S.H.Y.” ridiculed the Dublin police, mocked the ITGWU and militant Irish trade unionists, and depicted James Larkin as a ruinous white elephant in his memorable “Irish Zoo” collection. Earlier in 1913 the same artist had disparagingly referred to Larkin in cartoons as an ‘old patched up gas-bag’ and ‘strike monger’.

In October 1913 the Lepracaun observed sarcastically that ‘the sympathetic lock-out as an infallible cure for the sympathetic strike’ was failing to be the great success claimed by the employers of Dublin. The following month the publication was equally forthright in its reaction to the hysteria caused by the ITGWU’s ill-fated attempt to assist in the temporary transfer of Dublin working-class children to foster homes in Britain until the labour dispute had ended:

… it takes such scares as “kidnapping,” “abduction,” “deportation,” etc., to wake up Dublin to the fact that there are a few thousand unclad, unwashed and unfed nippers in our midst, many of whom are graduating in our Slum University for the degree of hooligan and who will in the near future provide a highly remunerative business for lawyers, magistrates, judges and similar pillars of society. Suppose that, by some horrible incantation, these juveniles were transformed into healthy, self-respecting, industrious citizens, what an appalling calamity it would be to the higher professions.

In its November 1913 issue the Lepracaun reacted to the news that James Larkin had been sentenced to seven months hard labour for sedition and incitement to riot and robbery by wondering aloud what jail sentence Sir Edward Carson would receive. As further proof that ‘the Lady of the Sword and Scales is a dilapidated old light-weighter’ which didn’t serve a purpose anymore, in its 1913 Christmas Number the Lepracaun observed that the recent habit of Dublin judges ‘discharging defendants [i.e. armed ‘scabs’] charged with discharging revolvers in the crowded streets of the city seems an odd way of discharging justice.’

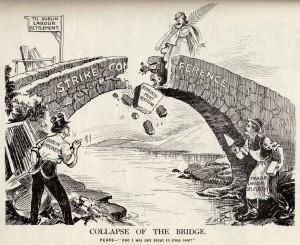

How did the Lepracaun react to the lockout finally petering out in early 1914? By noting that while the news was grateful and comforting ‘for the people in the life-boats’, it would be the Dublin ratepayers left to foot ‘the little bill’. This observation brings to mind O’Hea’s “Dublin, October, 1913” and “Flattening Him Out” cartoons, which in October and November 1913 had argued that it was the general public who suffered most during the great labour dispute.

Not that the Lepracaun ever lost its trademark sense of humour over matters. In the same issue an anonymous cartoon advised ‘freezing householders’ who were struggling financially to run up and down their stairs while carrying bags of coal upon their backs in order to warm their bodies to such an extent that they need not bother lighting an expensive fire!

http://

***

This gallery was created by James Curry, who completed a research placement at the Dublin City Library and Archive in 2014 as part of his Structured PhD in history and digital humanities at the Moore Institute, NUI Galway. nuigalway.academia.edu/JamesCurry

Further Reading

- James Curry, Artist of the Revolution. The cartoons of Ernest Kavanagh 1884-1916 (Mercier Press, 2012). http://www.mercierpress.ie/irish-books/artist_of_the_revolution_ernest_k…

- James Curry & Ciaran Wallace, Thomas Fitzpatrick and the Lepracaun Cartoon Monthly 1905-1915 (Dublin City Council, forthcoming, 2015).

- Francis Devine (ed.), A capital in conflict. Dublin city and the 1913 Lockout (Dublin City Council, 2013).

- Pádraig Yeates, Lockout: Dublin 1913 (Gill & MacMillan, 2013 edition).

http://