1913 Lockout was far more than just a curtain-raiser

It exposed contradictions that had to be worked through in independence, says Carol Hunt in today’s (January 27th, 2013) Sunday Independent

‘DORA Montefiore — she was young, she was opinionated, she was English and Jewish, she was a socialist; you couldn’t concoct a better hate figure for the Catholics [in Ireland]. And she was coming over here telling people what to do.”

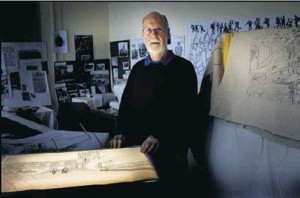

From his office in Liberty Hall, author, journalist and labour historian Padraig Yeates can point to the site of the old Tara Street baths and explain what happened when Dublin parents, desperate to have their sick and starving children taken to sympathetic homes in England (as suggested by Montefiore in consultation with James Larkin), went against the wishes of the Catholic Church and its allies.

“She came over [to Dublin] and they had a lot of mothers besieging Liberty Hall, the original building. They took the children over to Tara Street baths — to delouse them, give them new clothes — and when they came out there was a howling mob waiting for them, led by curates from Westland Row church, and they literally took the children off the parents to save them, or save their souls at least,” he adds drily.

As author of the seminal work Lockout : Dublin 1913 and the recently acclaimed A City in Wartime: Dublin 1914-1918 and A City in Turmoil: Dublin 1919-1921 (the trilogy will end with the Civil War), Yeates is part of the 1913 Commemoration Committee.

Though the events of 1913 are often dismissed as a “curtain-raiser” to the nationalist upheavals that followed, Yeates begs to differ. Not only was the social convulsion of the Lockout dramatic but, he argues, it exposed many of the contradictions that had to be worked out, often painfully, in independent Ireland.

Winners always attempt to control history, which may in some way explain why there has, so far, never been an official State commemoration of the events of 1913. Because undoubtedly, when the dust settled a decade after the Larkinite Lockout , it was obvious that Labour, in waiting, had sacrificed its advantage to the nationalist goal; its internationalist, socialist and pluralist aims suppressed by a conservative, Catholic, petit bourgeois ruling elite.

Yet a decade earlier — when the great Dublin Lockout united people from very different cultural and religious backgrounds — Yeates explains that things looked as if they might have ended differently: “It was a different way of looking at Ireland — it was looking at Ireland in relation to the rest of the world.

“From a trade union perspective obviously a big issue was union recognition,” he says. “Collective bargaining, workplace representation — but the Lockout was really much more than that. It was like a debate on the type of Ireland we would have, and it was really the only debate we had — because if you think about it, the 1916 Proclamation was written by a couple of people and plastered up on walls; the Dail debates were dominated by the Treaty; the Democratic Programme was read out in the First Dail but never debated.”

I ask did the comprehensive defeat of the workers — 20,000 of whom had gone on strike or been locked out — signal the end of that debate?

“It was the beginning of the end. It was a major defeat — the people on the strikers’ side were socialists, secularists, pluralists, people who supported women’s suffrage.

“Larkin and his ilk, trades unionists, were seen as secularist — that was part of the debate.” (Although as well as being the only self-professed communist to sit in Dail Eireann, Larkin was

paradoxically also a practising Catholic.)

“The fact that William Martin Murphy and his allies won that debate and that battle was an indication of the type of society we were going to have; Catholic, conservative, grasping. . .”

Murphy is seen as the central “baddie” of the period, uniting 400 employers against Larkin’s ITGWU, yet as Yeates wrote in an earlier essay: “It is ironic that a man who created so much employment, was generally regarded as a good employer, and who had acted in his time as an arbitrator in major trades disputes should be remembered for imposing a ‘Carthaginian peace’ on the city’s workers.” (Also conveniently forgotten is his support for the nationalist cause and his facilitation of the rise of Sinn Fein.)

On the difference between Larkin and his fellow socialist James Connolly — whom Yeates insists was very influenced by Pearse — Yeates notes: “Larkin always belonged to that broader Labour stream. He always organised Labour as a collective way of doing things. Whereas 1916, whether you agree with it or not, was an elite project: a group of people saying ‘we know what’s best and every one will follow’ — and they were right and you can’t argue with that.”

On the need for State recognition of the importance of 1913 and Larkin’s contribution, Yeates is hopeful. “We have had positive indications from ministers Jimmy Deenihan and Eamon Gilmore, and we have agreed in principle that there will definitely be an official State commemoration this year on August 31, the date of the original Bloody Sunday.” (When members of the DMP and RIC turned their batons on a harmless crowd — surprised at the appearance of Larkin on a hotel balcony — in O’Connell Street and injured between 400 and 600 of them.)

We walk to a building on Tara Street where the 1913 Lockout Tapestry is being put together by volunteers — schools, community groups, trade unions — in a project commissioned by SIPTU and the National College of Art and Design (Brendan Byrne is project manager). Committee member Michael Halpenny tells me later that he got the idea from a tapestry he saw in Scotland about Bonnie Prince Charlie’s rebellion of 1745. For the Lockout Tapestry, artists Cathy Henderson and Robert Ballagh are creating a visual narrative of the period.

He says: “It tells the story of the working people and the city in 1913. The first panel shows a candle lit. . . and the last panel a torch to be handed on. . . to working people everywhere.”